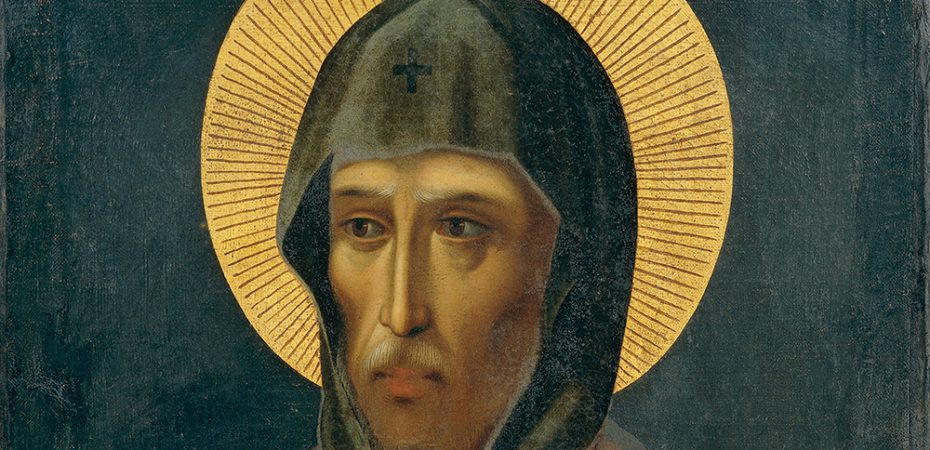

‘Harp of the Holy Spirit’

St. Ephrem left the Church a wealth of writings, hymns

Carlos Briceño Comments Off on ‘Harp of the Holy Spirit’

To poets, words are like dynamite. When used with precision, they blast with beauty and meaning, exploding in readers’ minds like a fireworks display during the Fourth of July. To understand the genius of St. Ephrem’s way with words, consider this hymn he wrote about the Blessed Mother:

“The Lord entered her and became a servant; the Word entered her and became silent within her; thunder entered her, and his voice was still; the Shepherd of all entered her; he became a Lamb in her and came forth bleating. The belly of your Mother changed the order of things, O you who order all! Rich he went in, he came out poor: the High One went into her, he came out lowly. Brightness went into her and clothed himself and came forth a despised form. … He that gives food to all went in and knew hunger. He who gives drink to all went in and knew thirst. Naked and bare came forth from her the Clother of all things [in beauty]” (Hymn De Nativitate).

When the word of God exploded in Ephrem’s heart, it set him on the path to becoming a great poet/hymnographer and an eloquent theologian and defender of the Faith. He was also a humble deacon, completely dedicated to serving others.

St. Ephrem was born in 306 in Nisibis (in modern-day Turkey). According to Pope Benedict XV, Ephrem was not very saintly as a youth. “He was hot tempered, easily angered, quarrelsome and unrestrained in mind and language,” wrote the pope in Principi Apostolorum Petro, a 1920 encyclical, which conferred onto St. Ephrem the title of Doctor of the Church, the only Syrian and deacon to receive that honor. “But while in prison on a false charge, he began to despise human things and the empty joys of this world” (No. 6).

After he was exonerated, Ephrem became a monk and devoted himself to piety and the study of sacred Scripture. St. James, the bishop of Nisibis, became his patron, and Ephrem taught at the theological school there.

Known as the “Harp of the Holy Spirit,” Ephrem was a prolific writer/composer.

“He wrote gorgeous hymns that are not just gorgeous, but theologically are incredibly profound,” said Jeffrey Wickes, an assistant professor of early Christianity at St. Louis University, who learned Syriac, which Ephrem used, to understand the saint’s writings.

It’s estimated Ephrem wrote more than 3 million lines of verse. He wrote biblical commentaries, poetic prose and homilies in verse and hymns. His preaching and writings were often aimed to counteract heresies and defend the dogma of faith.

Wickes said despite being celibate Ephrem never shared why he decided to remain a deacon or why he felt called to be one. Instead, in typical humble fashion, Ephrem referred to himself as a “herdsman” or “sheep herder,” which was a “poetic way of referring to the diaconate at the time,” Wickes added.

As another example of Ephrem’s humility, Wickes said Ephrem didn’t think too highly of some of the men who sought the priesthood or became bishops.

|

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe now.

|

“In fact, he complained that the controversies in the Church came down, ultimately, to what bishops were doing,” Wickes said. “He was very harsh on bishops. So, it is that easy to assume that he remained a deacon because he was humble.”

There also may have been a pragmatic reason: Deacons often were involved in music of the Church then, Wickes said.

St. Ephrem died in 373, and his death was an example of a deacon living out his call. A plague and famine had erupted in Edessa in what is now Turkey, and some people were hoarding food. Their excuse was that there wasn’t an honest person who would distribute the food in a fair manner. St. Ephrem volunteered, and no one disagreed with him because of how highly he was respected. He eventually caught the plague, which led to his death.

“Thus,” said Pope Benedict XVI about St. Ephrem in 2007, “the common and fundamental Christian identity appears in the specificity of his own cultural expression: faith, hope — the hope which makes it possible to live poor and chaste in this world, placing every expectation in the Lord — and, lastly, charity to the point of giving his life through nursing those sick with the plague.”

CARLOS BRICEÑO is the editor of Christ is our Hope, the magazine for the Diocese of Joliet, Illinois. He is a longtime journalist whose work has appeared in Our Sunday Visitor, the National Catholic Register and Vatican Radio.