Always Leave an Opening for Hope

Elements of an effective and sensitive homily on abortion

Stephen Fahrig Comments Off on Always Leave an Opening for Hope

“I never preach on abortion, because there might be women in the congregation who’ve had an abortion, and I don’t want them to feel bad.” A priest said this in my presence about 10 years ago, and his words have stuck with me for the last decade — not because I agree with them, but because they represent what I consider an example of well-meaning but misplaced pastoral sensitivity.

Let me be clear from the outset: Pastoral sensitivity is not only commendable but essential when dealing with the topic of abortion in a homily. Many women who have had abortions profoundly regret what they have done, feel intense guilt and shame, and even suffer from post-abortion trauma, a condition that most secular therapists sadly refuse to acknowledge. Even if a woman has confessed her abortion, received sacramental absolution and accepted to a greater or lesser extent that God has forgiven her, residual feelings of guilt can last for years, if not a lifetime.

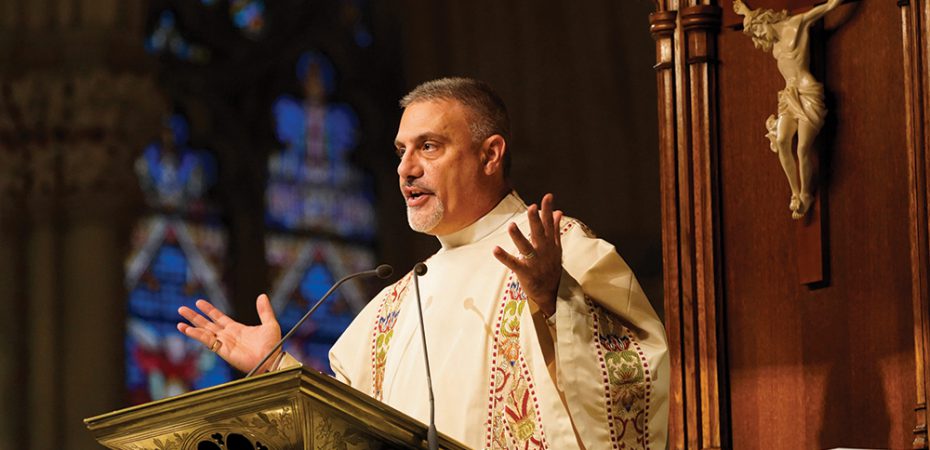

Statistically, it is likely that in any Catholic congregation (especially on Sunday) there will be at least one woman in attendance at Mass who has had an abortion. Given this tragic reality, a deacon who is preparing to deliver a homily on the issue of abortion must anticipate the likelihood that women who fall into this category may be present when he preaches, and craft his message accordingly. His words ought never to be delivered in such a way as to exacerbate already-present feelings of shame or trauma.

Nevertheless, this legitimate pastoral concern does not excuse clerics from preaching about pro-life issues or decrying the moral evils of abortion, euthanasia and other offenses against the dignity of human life. Indeed, there are times when discussion of these issues can be a pastoral necessity. An obvious example would be on or around Jan. 22, the anniversary of the Roe v. Wade decision that legalized abortion in the United States.

At other times, it may be that themes in the Mass readings converge with events in the news in such a way as to prompt a homilist to craft a message focused on the sanctity of human life. When the occasion arises, the preacher should not shy away from the Spirit’s promptings to address pro-life concerns for fear of causing hurt or offense. He should, however, be solicitous to express his message appropriately.

Crafting the Message

How might a deacon-homilist craft an appropriate pro-life exhortation? I humbly offer a couple of suggestions, taking a cue from Pope Francis’ thoughts on preaching in his apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium. First, begin with the positive; and second, when addressing the negative, always include an opening for hope in God’s mercy and forgiveness.

Toward the end of his lengthy treatment of the topic of preaching in the third chapter of Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis laments, “Some people think they can be good preachers because they know what ought to be said, but they pay no attention to how it should be said” (No. 156).

He goes on to emphasize the critical importance of positivity in developing an effective homily: “Another feature of a good homily is that it is positive. It is not so much concerned with pointing out what shouldn’t be done, but with suggesting what we can do better. … Positive preaching always offers hope, points to the future, does not leave us trapped in negativity” (No. 159).

The pope’s words here are especially relevant when it comes to preaching on life issues. One must always bear in mind that the pro-life message is not just about condemning abortion, euthanasia, etc., but about inculcating positive respect for the dignity of human life.

The Church seems to recognize this reality in her liturgical texts. For example, the Roman Missal contains a votive Mass “For Giving Thanks to God for the Gift of Human Life.” The collect for this Mass articulates pro-life concerns in a very positive and attractive manner: “God our Creator, we give thanks to you, who alone have the power to impart the breath of life as you form each of us in our mother’s womb; grant, we pray, that we, whom you have made stewards of creation, may remain faithful to this sacred trust and constant in safeguarding the dignity of every human life.”

A homily based on this beautiful prayer could be a very effective way of accentuating the Good News aspect of the Church’s concern for protecting the rights of the unborn. (As an aside, when preparing to preach, every deacon should not only consult the Scripture readings of the day but the other Mass texts, including the collect and the preface. Although my bias as a biblical theologian is toward scripturally-based preaching, I do like to remind seminarians and deacon candidates that the General Instruction of the Roman Missal allows a homily to be given not only on the readings but also on “another text of the Mass.”)

Addressing Evil Head-on

The importance of positivity notwithstanding, it is nevertheless true that there are times when evil has to be addressed head-on. Pope Francis himself has regularly decried a “throwaway culture” in which the elderly and the unborn are regarded as nuisances to be eliminated by means of euthanasia and abortion; he has even gone so far as to compare procuring an abortion to hiring a hitman! While one might legitimately question the pastoral sensitivity of that particular analogy (or at least be cautious about quoting it without nuance in a homiletic context), the pope’s blunt words do serve as a reminder that there are times when grave moral evils must be confronted and condemned.

As ordained ministers charged with preaching the Gospel, deacons must see themselves as sharing in Christ’s prophetic ministry, a key component of which is taking a prophetic stance against societal evils. Just as the biblical prophets did not shy away from boldly challenging the predominant sins of ancient Israelite society, so preachers today must not hold themselves excused from addressing the evils of the contemporary culture.

Nevertheless, there is wisdom in Pope Francis’ admonition that even when a homily “does draw attention to something negative, it will also attempt to point to a positive and attractive value, lest it remain mired in complaints, laments, criticisms and reproaches” (Evangelii Gaudium, No. 159).

The Sense of Hope

This leads to the question of how one might give due weight both to the legitimate condemnation of moral evils on the one hand and the need for pastorally sensitive positivity on the other. It is here that the biblical prophets of the Old Testament provide a helpful model for deacons and other clergy. Now it must be acknowledged that the prophetic writings of the Bible often have a somber tone, with some works like Amos seeming almost unremittingly grim.

However — and herein lies the lesson for the contemporary preacher — it is also almost universally true that the Old Testament prophets, despite whatever negativity or even ferocity might sometimes characterize their oracles, never leave their audiences without a sense of hope.

The same Jeremiah who boldly prophesied the destruction of Solomon’s temple and the exile of his fellow Jews to Babylon also held out the hope of restoration in what many consider to be one of the most beautiful and hopeful passages of the Old Testament (cf. Jer 29:10-14).

The same Amos who spoke almost exclusively of the coming destruction of the northern kingdom of Israel nevertheless concluded his oracles with a promise of future hope (cf. Am 9:11-15).

The same Zephaniah whose prophecies of doom and gloom inspired the famous Dies Irae requiem chant also concluded his prophetic oracles by exhorting his audience “Do not fear, Zion, be not discouraged!” and assuring them that God was in their midst, working for their good (cf. Zep 3:16-20).

In a similar vein, parishioners leaving Mass after hearing a compelling homily on abortion may be able to say that the same Deacon Joe or Deacon Bob who forcefully condemned the murder of unborn children also offered a compassionate message of hope for women who have had abortions and are still in need of healing.

Boldness

A preacher who has the boldness to address a polarizing topic like abortion in his homily in the first place must also have the sensitivity to acknowledge the possible presence in the congregation of abortion’s other victims — namely, the women who have had them and the husbands, boyfriends, parents, etc., who may have been involved in a woman’s decision to end her pregnancy.

He might begin by discussing the reality of post-abortion trauma, pointing out to everyone present that those who have been involved with abortion often experience tremendous psychological and spiritual suffering as a result — a suffering, moreover, which the secular world generally refuses to acknowledge for what it is.

Then he might say something along the lines of: “I know that there may be women here at Mass today who have had an abortion in the past. There may be men here who once pressured their girlfriends or wives into doing so. If there are, please know that my words this morning are not intended to condemn you, but to offer hope for forgiveness and healing …”

This could be followed by a reminder that no sin is beyond God’s capacity to forgive, that reconciliation is available through the sacramental ministry of the Church, and that organizations like Project Rachel exist to facilitate the process of post-abortion healing. These are words that may seem obvious and even trite to many of us, but to someone who is deeply wounded they may be a spiritual lifeline if delivered with sincerity and compassion.

Genuine Sensitivity

“I never preach on abortion, because there might be women in the congregation who’ve had an abortion, and I don’t want them to feel bad.” I began this reflection by quoting these words of a well-meaning priest whose pastoral sensitivity had convinced him to remain silent about one of the gravest moral evils in our contemporary society.

I hope that the deacons (and other clerics) who read this essay might come away more emboldened to preach on abortion, albeit in a spirit of genuine sensitivity toward those who are suffering from post-abortion trauma.

I hope this contributes in a small way to fostering a culture of authentic pro-life preaching, in which more and more clergy are heard to say, “I regularly preach on abortion when the occasion warrants it … because there might be women in the congregation who have had an abortion, and I want them to know that God is waiting to offer them his mercy, forgiveness and healing.”

STEPHEN FAHRIG, STD, is associate professor of biblical theology at Kenrick-Glennon Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri, and an instructor in the permanent diaconate program for the Archdiocese of St. Louis. He is a candidate for the diaconate.