Deacons as Guardians and Promoters of the Animating Mystery of Christ

A deacon must carry the Gospel of Blood to the corners of the world

Deacon James Keating Comments Off on Deacons as Guardians and Promoters of the Animating Mystery of Christ

The following is Part 1 of an In Focus on the Blood of Christ and the role of deacons. This essay was the inaugural Mitchell Lecture for the Institute for Diaconal Renewal at Franciscan University of Steubenville.

Within the Rite of Ordination, the deacon is given the Book of the Gospels from the bishop. The reception of the Book of the Gospels symbolizes the deacon’s mission. Each Sunday after his ordination, the deacon proclaims this Gospel as its ordinary minister and occasional preacher. Then, upon the conclusion of the Eucharistic liturgy, the deacon is positioned to follow the laity out of the church building and live among them as an envoy of the servant mysteries of Christ.

This life among the laity is signaled in the dismissal rite of the Mass when the deacon urges the laity, and himself, to, “Go and announce the Gospel of the Lord.” This diaconal going forth to live holy orders within a lay lifestyle carries a mystery of grace. This grace elicits an evangelical response from the laity. It is the hope of the Church that, by placing clerics among the laity in their daily lives, this grace will support their efforts to appropriate the power of the Eucharist in their mission to transform culture.

Both the grace of holy orders in the deacon and the grace of the Eucharist and baptism in the layperson cooperate to ignite evangelization within the nooks and crannies of secular culture. The deacon embodies a particular calling to “abide” in the secular world. He is a cleric living a lay lifestyle for one reason alone: to animate and support the evangelical and martyrological mission of the laity.

Sacred Blood as Life-giving

While the diaconal mission of proclaiming the Gospel at the liturgy assists the laity to internalize the Good News, the more subtle liturgical duty of the deacon to prepare, guard and distribute the precious blood of Christ serves the laity in their mission to give witness (martyrdom) to Christ in culture. The General Instruction of Roman Missal says, “At Mass the deacon has his own part in proclaiming the Gospel, in preaching God’s word from time to time … in preparing the altar and in serving the celebration of the Sacrifice, in distributing the Eucharist to the faithful, especially under the species of wine” (No. 94).

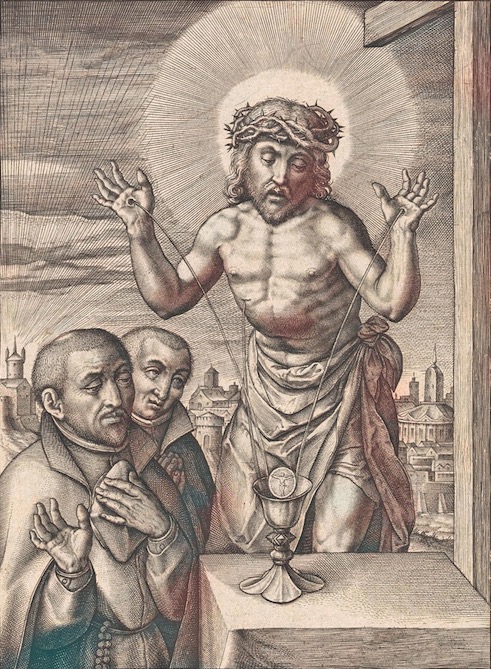

Chalice” by Hieronymus Wierix and Piermans circa 1563. Gibon Art / Alamy Stock Photo

It is Christ’s own blood that animates the laity — the Church — keeping her vibrant, vigorous and vital within daily life. The liturgical minister who mediates the source of this animation is the deacon.

In Mark’s Gospel, the sons of Zebedee are asked, in response to their mother’s request that they should sit beside him in his kingdom: “Can you drink the cup that I drink or be baptized with the baptism with which I am baptized?” They reply that they can and [Christ replies], “The cup that I drink, you will drink, and with the baptism with which I am baptized, you will be baptized” (cf. Mk 10:38-9).

It is in receiving the Blood of Christ that believers are given the strength to remain faithful to their call to publicly witness to the Gospel. As Cyprian of Carthage noted, “How can we instill in them the strength to drink the cup of martyrdom if we do not first permit them to drink of the cup of the Lord in the Church?”

At the ancestral source of the diaconate, the Levitical priesthood in the Old Testament, we meet the inchoate origins of a deacon’s ministry around the altar. The Prayer of Consecration in the diaconal ordination rite says: “You established a threefold ministry of worship and service for the glory of your name. As ministers of your tabernacle you chose the sons of Levi and gave them your blessing as their everlasting inheritance” (No. 21).

It was the Levites who assisted the priests in preparing the sacrifice of bulls, goats and sheep. In the Old Testament, the sprinkling of blood was a medium for consecration, an act of setting people aside for service to God. The victim was slain in order that its life, in the form of blood, may be released. Furthermore, its flesh was burnt in order that it might be transformed as an offering, a life presented in reverence to God.

Sacredness

For the Hebrews, blood was sacred, as it carried life from God to the living thing; thus blood sustained life. At liturgical rituals in the Old Testament, the priests understood life to be contained in the blood, and so it was not to be ingested. Rather, in reverence to God, life’s author, it can only be poured upon the earth, upon the people and upon the altar (cf. Dt 12:23-24; Lv 17:11). To the Hebrews, blood was a sign that life “belongs” to God and must not be profaned, not consumed.

While blood could not be ingested, it remained a powerful symbol in Hebrew life and ritual. Blood “marks” a man as God’s own, hence the Passover (cf. Ex 12), where no destruction came to the Hebrews if their dwellings were marked with blood on the doorpost. It was by means of blood that one’s life was not only spared but ordered toward a mission. It was through blood, the spiritual or vital principle, that God came into contact with people. The Hebrews understood blood to give life and even carry the “spirit” or the “breath” of the living thing.

In offering animal sacrifice to God, the priests and Levites of the Old Testament maintained ordered worship for the people. In this worship, people who desired order were willing to sacrifice animals to God in a mode of intercession, gratitude and fear. It was the Levites who prepared the altar during the preparation of the sacrifice. During the preparation of the sacrifice, it was the Levites who prepared the altar. The Levites also assisted with the purification of the temple and cleansed the “utensils” also needed for the sacrifice (cf. 2 Chr 29:15-18).

“Since there were too few priests to skin all the victims for the burnt offerings, their fellow Levites assisted them until the task was completed and the priests had sanctified themselves. The Levites, in fact, were more careful than the priests to sanctify themselves” (2 Chr 29:34).

Blood of Christ

The work of the priests and Levites, as those who offer life to God, came to its ultimate completion in the Paschal Mystery of Jesus Christ. Now, Christ is the one sacrifice that unites God and humanity. His is a perfect offering of love and obedience, reconciling humanity to God the Father in ways bulls and sheep could never attain. Here on the altar of Calvary, the inner life of God, which the Hebrews sought to understand and did so only as in a mirror darkly (cf. 1 Cor 13:12; Heb 1:1-3), is now clearly revealed in its fullness.

The inner life of God is self-donating love, a dynamism of giving and receiving love within God himself, now revealed in Christ’s own life poured out upon the altar for the “many” (cf. Mt 20:28). It is this Trinitarian love now revealed in Christ upon Calvary, which reconciles God and humanity. It is the vocation of those who participate in “the death of the Lord until he comes” (1 Cor 11:26), the baptized, to become servants of divine reconciliation by their public witness.

Deacons are sent to the remote corners of society to catch the baptized up into this flowing divine life; a life sourced in Christ’s own blood and sacramentally celebrated as divine life itself is shared. “From the pierced heart of Jesus rivers of graces were to be poured out upon the world to sanctify the Church,” writes Blessed Columba Marmion in “Christ in His Mysteries.”

It is the deacon who assists in distributing these graces during the Liturgy of the Eucharist in the Communion rite and embedded in the liturgy of charity — that is, his ministry among the laity. The deacon lives among those who participate in the life blood of God’s own self-gift, helping to assure that their love does not grow cold and that their devotion to the Eucharistic mystery yields effective public witness.

In light of the sacrifice of Christ upon the cross, consuming blood during worship, albeit under the form of wine, is no longer a contradiction to the ways of the Hebrew priests and Levites. Consuming “blood” is no longer an affront to God in that he willed that communion with the Divine be effected as such: “Unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you do not have life within you” (Jn 6:53).

Sacramental consummation becomes a way to participate, liturgically, in “life and have it more abundantly” (Jn 10:10). Since the sacrifice of Christ is intended to be divine love shared, there is no blasphemy or insult in sharing his blood, as it is the reality, which affects and signifies this communion with God. Hence, consuming God’s life as Precious Blood is not a communion trespassed, but one that is fulfilled. The blood of the Eucharistic cup is identical to the charity of God.

Blessed Marmion wrote that it is in drinking from the chalice of his Divine Blood, from which we share in God’s joy, that we “excite charity” in our lives. In the liturgy, the deacon is the custodian of the blood and the chalice. It is fitting that he serve the chalice so as to excite charity in the Church’s members and reaffirm his own calling to bear the love of Christ to those in need.

The Hebrews believed that it was by way of blood that God comes in direct contact with bodies. The deacon, the consecrated one who cares for the Precious Blood, is called to “come in contact” with the Body of Christ, the Church, in its spiritual and human needs. This is known as ministry.

The Body of Christ, the Church, draws life from the “vine” (cf. Jn 15:4), the very mystery of Christ’s life, death and resurrection. Such spiritual life is sustained by abiding in faith, hope and love. This faith, hope and love needs to be nourished at the source of holiness, even while one engages in the work, commitments, joys and failures of ordinary life.

If the Church fails to receive such nourishment, then the blood of Christ, the Eucharist, does not flow through the culture. Only when the laity bears witness to the body and blood of Christ that consumes them within Eucharistic participation can we say that the world has hope of being evangelized.

DEACON JAMES KEATING, Ph.D., is a professor of spiritual theology at Kenrick Glennon Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

EXPLORING A PARADOX

Pope Benedict XVI, in Sacramentum Caritatis, echoes St. Augustine’s “Confessions,” and speaks of the Blood of Christ flowing through the sacramental world wherein the means of grace received absorbs the recipient instead of the recipient absorbing what has been received.

He writes: “By receiving the body and blood of Jesus Christ we become sharers in the divine life in an ever more adult and conscious way. … Stressing the mysterious nature of this food, Augustine imagines the Lord saying to him: ‘I am the food of grown men; grow, and you shall feed upon me; nor shall you change me, like the food of your flesh, into yourself, but you shall be changed into me.’ It is not the eucharistic food that is changed into us, but rather it is we who are mysteriously transformed by it. Christ nourishes us by uniting us to himself; ‘he draws us into himself’” (No. 70).

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………