Formed in the Image and Likeness of Christ the Servant

A deacon’s formation into Christ the Servant needs to be ongoing

Deacon Anthony J. Clishem Comments Off on Formed in the Image and Likeness of Christ the Servant

Have you ever had this verbal exchange: “What’s going on?” You reply, “Same old same old!” After this friendly, harmless encounter, you both smile and go on your way.

The same question can also have a social dimension. In 1971, American singer-songwriter Marvin Gaye released his hit single “What’s Going On.” He wrote it in response to the police brutality and racial strife that all Americans were witnessing during that turbulent time. We might ask the same question about today’s social upheaval: “What’s going on? Same old same old!”

For faithful Christians in the Church, and in particular for her deacons, what’s going on is never about the same old same old. In the prophetic words of Isaiah, we hear the Lord say, “See, I am doing something new! / Now it springs forth, do you not perceive it?” (43:19). For deacons, perhaps the best reply to the question “What’s going on?” is simply, “What’s ongoing!” In other words, what we should always be about is our ongoing formation into Christ the Servant, the slave of all.

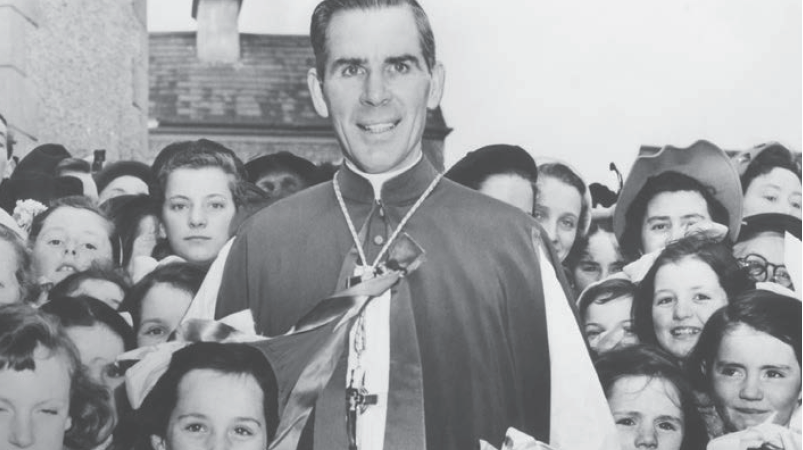

If a deacon’s formation into Christ the Servant is to be ongoing, then the retelling of that formation would be something like an autobiography. Venerable Fulton J. Sheen knew this when deciding on a title for his autobiography “Treasure in Clay” (Ignatius Press, $17.95). In choosing this title, the archbishop realized that his formation into the priesthood was fundamentally interior and ongoing. Some further explanation will help us see the applicability of Sheen’s insights to ongoing diaconal formation.

Retrospective Story

As deacons, we can only tell the story of our formation retrospectively. If I were tasked to write that story, the first problem would be to decide on a beginning. When did my formation in diakonia actually begin? Did it start with diaconal instruction in my diocese, or at the moment I first heard the specific call to be a deacon? When did, or when will, that story come to an end — at ordination, or at some future moment in time? More importantly, would I be able to tell the true and complete story?

On the first page of Sheen’s autobiography, he makes a remarkable admission: “[This] is not my real autobiography.” The reader notices the clever, rhetorical quip. In typical Sheen-like fashion, he uses the device to ask more profound questions: How does one tell the true story of a life? What is the essence of that formation that molds one into the person he is meant to be?

Sheen’s autobiography arrived in bookstores a few short months after he died. In titling it, he borrowed an image from St. Paul’s Second Letter to the Corinthians: “But we hold this treasure in earthen vessels, that the surpassing power may be of God and not from us” (4:7).

He explained, “I have chosen this text to indicate the contrast between the nobility of the priesthood and the frailty of the human nature which houses it.” Elsewhere he added, “The treasure comes from God; the clay gives the response.” “How, then, do I see my life?” he asked. “I see it as a priest.” He also said, “I can never remember a time in my life when I did not want to be a priest.”

Dimensions of Formation

I did not always see myself as a deacon. The formation I received as a university student provided some shaping to the vessel I would later become. After college, I would continue to discern the many yearnings of my heart. A discernment of the priesthood and religious life came and went. The need to grow and mature was provided for by the many mentors I sought out.

The longing for companionship and responsibility was met by the gift of wife and children, and their needs offered the opportunity for me to grow pastorally, as head of a domestic church. And as my career in education provided for the material needs of my family, it also fed my desire for ongoing intellectual formation. Practicing my Catholic faith kept me on a spiritual path as I sought greater meaning and purpose in my life.

Looking back, I recognize that long before my acting on the call to enter diaconal formation, I was already being formed across four dimensions: intellectual, human, pastoral and spiritual. Yet there was still another, more fundamental longing in my heart.

In 1998, 20 years before my diaconal ordination, the Vatican’s Congregation for the Clergy published its Basic Norms for the Formation of Permanent Deacons, referring to the ongoing formation of the deacon as “first and foremost a process of continual conversion” (No. 65). Once ordained, I knew that each dimension of formation could provide an opportunity for conversion, a process meant to make me more like Christ the Servant. “So be perfect,” he commanded us, “just as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Mt 5:48). But how can clay ever come close to treasure?

To answer this question, we return to Archbishop Sheen and his disclaimer that “Treasure in Clay” was not his “real autobiography.” If not that edition, then which? He explains that there is a real one written 21 centuries ago: “The ink used was blood, the parchment was skin, the pen … a spear.”

“That autobiography is the crucifix — the inside story of my life. … My life, as I see it, is crossed up with the crucifix.”

“Only the two of us — my Lord and I — read it, and as the years go on, we spend more and more time reading it together.”

Venerable Sheen saw his formation as existentially linked to the story of Christ the Priest. If so, then would it not also hold for every deacon — namely, that the story of one’s diaconal formation is linked to the story of Christ the Servant — the story that only he and I can read together?

So, Too, the Diaconate

Sheen saw his life in three stages. The first was his call to the priesthood, which he said was the Lord’s “first look” into his soul. With this call, he experienced his unworthiness of the priesthood. This, too, we may experience in our call to the diaconate. Sheen notes that God allows this, that the “power may be of God and not from us” (2 Cor 4:7).

He identified the second stage as his resistance to the cross. “I was a priest,” he writes, “without being a victim.” What part of Christ the Servant are we most inclined to resist? Have we not too often become deacons who resist the enslavement of servitude? Could I lower myself to wash the feet of every man, even my known denier or betrayer?

The third stage of his life Sheen called the “Second Look,” referring to the eyes of the Lord looking at Peter as the cock crowed. It was the look of mercy and compassion, as if to say, “I know, I know. It is why I washed your feet!” For the deacon, to be configured to Christ the Servant is to be the vessel that holds that treasure of mercy — the mercy that only Christ can give. Like Peter, we falter. We are clay, and our formation is ongoing.

After the Second Vatican Council, Sheen must have had a special interest in making the door open wide for the reinstitution of the permanent diaconate in the United States. On June 1, 1969, at the age of 74, he ordained the country’s first permanent deacon, a 34-year-old former Anglican priest, husband and father of four.

The same old had become something new.

DEACON ANTHONY CLISHEM serves as the Office of Catechetical Formation leader for the Diocese of Joliet, Illinois.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Deacon Clishem Recalls His First Encounter with a Deacon

In 1979, the year Fulton Sheen finished his autobiography, I had my first encounter with a deacon. At the time, I was a senior at the University of Notre Dame, finishing my degree and struggling to discern God’s will for my life. From my perspective, I was, I admit, a bit of a mess, like a lump of unformed clay.

In the winter of that year, I signed up for a two-day “Urban Plunge,” a program offered by the University’s Center for Social Concerns. Together with a small group of young, like-minded, idealistic Catholics, we spent two days of our Christmas break in our hometown (Louisville, Kentucky) where our sponsor, a priest who lived and worked in the inner city, gave us an inside look at life and ministry among the urban poor.

On one of our many stops, we met a deacon who ran a soup kitchen on the city’s west end. He took a break from his busyness to speak with us about the Church’s work with the poor. During this interaction, it became clear to me that those who worked at the soup kitchen were encountering Christ in the people they served. And I was struck by the humble, hidden service of this deacon to those who had nothing to offer but their poverty and need.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….