What’s a Deacon to Do?

How we can mobilize a revolution in tenderness

Deacon Timothy E. Healy and Dr. Jeffrey J. Froh Comments Off on What’s a Deacon to Do?

With the diocesan phase of the 2021-2023 synod process complete, related to the upcoming 2024 Church’s Synod on Synodality, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops recently released the National Synthesis of the People of God in the United States of America (the synthesis). It reflects the contributions of hundreds of thousands of U.S. Catholics.

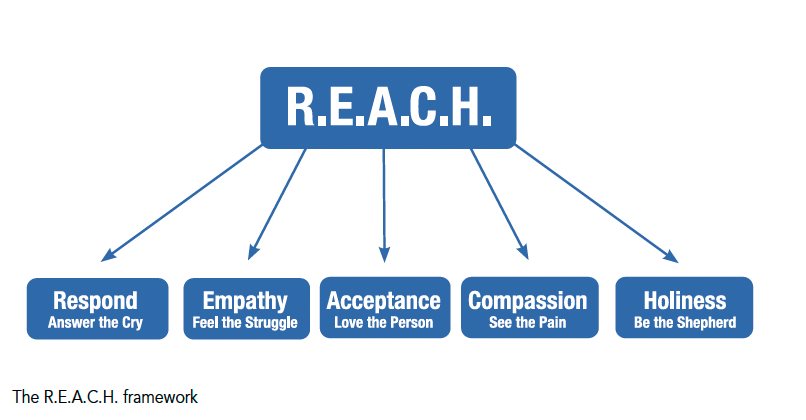

When read along with the latest National Directory for the Formation, Ministry and Life of Permanent Deacons in the United States and other papal documents, the urgency for deacons to reach more people emerges. But what are the most striking problems, perceptions and challenges the synthesis revealed that prevent us from reaching people? And is there a practical framework (R.E.A.C.H.; see below) that we deacons can use to build constructive responses to these challenges? (Quoted matter in the following five points are from the synthesis)

1. “The sin and crime of sexual abuse has eroded not only trust in the hierarchy and the moral integrity of the Church, but also created a culture of fear that keeps people from entering into relationship with one another and thus from experiencing the sense of belonging and connectedness for which they yearn.”

2. Polarization and marginalization, especially of women, minorities, the LGBTQ community, immigrants and other socially excluded groups “have exposed a deep hunger for healing and the strong desire for communion, community, and a sense of belonging and being united.”

3. “A significant percentage of participants also indicate that receiving Eucharist does bring them more closely in solidarity with the poor. Suggestions on building communion around the Eucharist include items such as warmer hospitality, healing services, and more invigorating preaching by clergy.”

4. “Practically all synodal consultations shared a deep ache in the wake of the departure of young people and viewed this as integrally connected to becoming a more welcoming Church. … Young people themselves voiced a feeling of exclusion. … Young people’s waning participation in parish life was a source of great pain for many older community members. They lament the departure of young people with anxious concern: ‘I feel like a failure because I was not able to hand down my faith to my children who are now adults.’ ‘It breaks our hearts to see our children that we brought to Mass and sent to Catholic schools and colleges reject the Church.’”

5. In concluding remarks on discernment, the document said that the Spirit leads us to “local, attentive listening to one another within and outside of the Church; participation, honesty, and realism; and a continued willingness to learn accompany discernment. The rediscovery of listening as a basic posture of a Church called to ongoing conversion is one of the most valuable gifts of the synodal experience in the United States.”

The challenge to deacons is to do whatever possible for people to trust us and have faith in our moral integrity. If successful, we can then address their sense of fear, marginalization and exclusion — and maybe even help them overcome it.

We can do this if we focus on the human desire to be heard — really heard — and be the “ears” that many think have become deaf. The poignant desire expressed in the synthesis for more young people to embrace God expresses every hearts’ craving for connection, love and faith in the Church. Pope Francis encourages us to embrace this desire, and frequently calls for a “revolution in tenderness.” He describes it as “the love that comes close and becomes real. It is a movement that starts from our heart and reaches the eyes, the ears and the hands.”

Therein lies the key to meeting the challenges.

As deacons, it’s our mission — that we promised to undertake at ordination — to emulate Jesus and meet this need to be heard, this need to be loved, this need to be reached. How can we structure a personal and ecclesial response to the new challenges to this mission that the synthesis presents? How can we mobilize for this “revolution in tenderness”?

R.E.A.C.H. Framework

The R.E.A.C.H. framework outlined below describes how deacons can mobilize. It’s rooted in Scripture, our sacramental heritage and positive psychology.

R stands for respond. Specifically, how do we respond to the question, “Do you love me?” Every human heart yearns to be seen, encountered, understood, encouraged and loved. Conversely, it also yearns to be invited to see someone and to engage with someone’s life with acceptance and compassion, to put someone else’s interests ahead of its own and to help them thrive.

The synthesis offers ways for deacons to answer these “cries from the heart.” To start, deacons can help people feel heard, seen and cherished by being available, welcoming and authentically interested in people. Some deacons do this by volunteering for ministries like hospital or prison chaplaincy.

Others with the skills and a desire to use social media for outreach can appear on, or even create, a podcast or YouTube channel (think of Bishop Robert Barron and Father Mike Schmitz). Those deacons who like to write can create an article or book as I did when I wrote “Tales for the Masses” and “More Tales for the Masses” (CSS Publishing Company, $43.90 as a two-book set). Use your talents, strengths and treasures to answer that poignant question, “Do you love me?” with a vivid “Yes!”

Even in secular environments, as the directory reminds us, we can tell people that we’re deacons (more with actions than words) who are calm, accepting and loving, and that we’re “open for business.” This entails knowing people’s names and listening to their stories with interest and compassion; being reachable by phone, email and certainly in person. This behavior screams “You matter!”

People might respect an extended hand — but they love open arms.

The national directory reminds us that the Church is a complex reality emerging from the coalescence of the divine and human. In a critical sense, making ourselves available as deacons makes the divine available to people in a special way, derived from our participation in the Eucharistic community. As the directory states, “Communion gives rise to mission and mission is accomplished in communion” (No. 22).

When people encounter us, it should be as if they encounter Jesus. When Jesus said, “This is my body given for you,” the implication for people in communion is then to say to one another, “this is my body (my presence) given for you (on your side and at your service).”

Some of us may struggle with responding to and connecting with people. This is partly because society often slaps away our outreached hand.

There may be other reasons, too. Let’s go under the hood for a moment. Psychologists, like my friend, Dr. Jeffrey Froh, tell us that much reluctance to “say hello first” is rooted deeply in our psyche. He says: “Maybe we often hesitate to connect with people because some of us have only had imaginary friends. Some of us went to the prom alone. And others are still waiting for dad’s approval or mom’s love.”

“Childhood experiences,” Jeff continues, “teach us that we’re loveable if our attempts at connection were met with smiles, not scowls. Some people, therefore, believe that they’re worthy of love and belonging — as is — and thus their attempts at future connection will likely be met with love. Others, however, believe that they’re unworthy of love and belonging because it’s conditional, based on what they do — not unconditional, based on who they are — and thus their attempts at future connection will likely be met with indifference (maybe even hate).”

If that sounds uncomfortably familiar, it’s because struggling with social connection is part of the human condition. “Everyone falls somewhere along the ‘worthy of love and belonging’ spectrum,” he says. “We all have ‘stuff’ that discourages us from being courageous and embodying discipleship. It’s better for us to embrace rather than deny this. Get help through spiritual direction or therapy, but don’t fret over it. Why? Because God is with us. The Spirit is within us. And Jesus is with us — holding our one hand while we extend to people our other hand.”

E stands for empathy. Empathy says, “I love you.” We have to look the part. Smile more (Deacon Tim’s wife’s phrase is, “Fix your face”); don’t ever give yourself permission to be supercilious, disdainful or aloof. In short, be the “parent” who gives the smile, not the scowl.

Along with our prayers of praise and thanksgiving, we deacons should habitually pray to be the expression of God’s love that we were created to be, so that when people see you, they see Jesus; when they hear you, they hear Jesus; and when they’re touched by you, they’re touched by Jesus.

You know when you’ve got the E right when people tell you you’re “the real deal,” when they stop to talk about something important with you, and/or when they ask you to help them with difficult issues in their lives. I hope that all of us get to hear at some point what people have told me in the hospital and elsewhere: “I’ll never forget you”; “I’m glad you were the one on call tonight”; “You have no way of knowing, but what you told us was exactly what we needed to hear”; and, even, “You saved my life.” Deep in my heart, I know that the “you” they’re referring to was Jesus, graciously working in, with and through me.

A stands for acceptance. Acceptance doesn’t mean something’s good, or the way we want it, or that it’s our desperate resignation to unavoidable circumstances. Acceptance is our unvarnished acknowledgment of what’s really happening; what has happened to me; what I sense is going to happen to me. Acceptance enables an infinity of possible responses — whereas denial eliminates them. The A in R.E.A.C.H. answers the questions, “Who am I, and who are you?”

To accept both yourself and other people is to refuse to judge. The synod was very clear about judgment. Marginalized people consistently report that they feel judged by us. In response, the synthesis urges that “we need to examine the way in which certain teachings are presented, to demonstrate that we can be faithful to God without giving the impression that we are qualified to pass judgment on other people.” In a word, lead with love.

If we’re uncomfortable with divorced people, volunteer with Retrouvaille. If we struggle understanding homosexuality, view “Desire of the Everlasting Hills” or volunteer with the Church’s Courage apostolate. People with drug addiction make you uncomfortable? Volunteer as a chaplain in a Catholic recovery group like Calix. Go where you’re uncomfortable, pray and be open to your healing.

Eventually, you’ll then become more comfortable with and accepting of God’s children, and, if you’re lucky, they’ll become more comfortable with and accepting of you.

C stands for compassion. The operative part of compassion for deacons is the witness we bear to God’s love expressed in Jesus Christ. It says, “Yes, we’ll ‘suffer with’ you, and bring you God’s love.”

To learn compassion, allow someone else to be compassionate to you. (Remember, though, that childhood experiences make some of us better at giving than receiving compassion.) Everyone’s hurting about something. Ask someone to walk with you through your own pain. Maybe it’s a therapist, a spiritual director, your wife or a good friend. In experiencing your helplessness and vulnerability, you’ll learn how to accompany others in experiencing their helplessness and vulnerability. That’s the only way we learn authentic compassion.

By accepting and loving our humanity, we can accept and love others’ humanity.

What about that “suffering with” part? It’s a bit like this: You may have read about the Ukrainian woman who found refuge in Germany after the Russians invaded. Soon after though, she chose to return to her homeland. “Why?” asked her friends. “I must save my mom,” she replied.

When people who cannot watch others suffer alone take action, as this Ukrainian woman did, that’s “other-compassion.” It’s why God became man: to share in our suffering, defeat the enemy and give us a path to salvation.

When it becomes difficult or frightening, we should consider what Jeff writes in his book, “Thrive: 10 Commandments for 20-Somethings to Live the Best-Life-Possible” (Human Touch Press, $14.95): “Whether we’re sinful or virtuous … God still protects us when we’re afraid, consoles us when we’re sad and holds us when we’re rejected. Reassuring us everything will be okay, and that we’re okay — as is. God’s love is the ultimate security blanket.”

Self-compassion (the flipside of the “compassion coin”) is a prerequisite for other-compassion. This is because we can’t give what we don’t have. Jesus tells us to give someone our “other cloak” if we have two. But what if we had none? Self-compassion, like a cloak, protects us from “storms.” It provides peace by giving us the permission to be human.

The permission to blunder. The acknowledgment that we’re normal when our inner critic calls us “weirdo.” Therefore, hug your inner child. Hug your heart. Hug your spirit.

The bigger the bear hug you give yourself, the bigger the bear hug you can give others.

H stands for holiness. To be holy is to be different. An unavoidable component of diaconal ministry is to be the one who contradicts the secular worldview of power, sex and self-absorbed hedonism with the good news of love, gentle kindness and joyful, self-forgetting service.

If no one hates you, thinks you’re one of those holier-than-thou snobs, or rejects you, it may be that you’re not doing the job right! If it feels uncomfortable, remember the God-Man on the cross and rejoice that you, too, have probably been rejected — like him.

When we connect our suffering to Jesus’ suffering, we’ll then better connect to others’ suffering.

Holiness comes with a price, paid for by hours spent in prayer. We strongly encourage our fellow deacons to adopt a contemplative, apophatic prayer practice in addition to the Liturgy of the Hours that we promised to pray. It’s nothing more than what Jesus teaches us in the Sermon on the Mount when he says we should enter our inner room, close the door and pray to the Father, who sees in secret.

Perhaps you’ll find that centering prayer takes you into your inner room, where Jesus resides and holiness blossoms. Others may find the Carmelite practice of gazing upon Christ in silent Eucharistic adoration gets the job done. We’d urge you to scan Robert Wicks’ “Prayer in the Catholic Tradition” (Franciscan Media, $39.99) to find a contemplative prayer practice with which you can be comfortable. That quiet, inner place in our heart is, after all, where our deepest yearnings live, and where we experience their satisfaction.

The synthesis threw down the gauntlet. Everyone in the Church is responsible for meeting the challenges identified. More than ever, we deacons need to master our mission to embrace all of God’s children and to embody Jesus. This requires that people see, hear and feel our love and compassion. So, as you prepare your next homily, remember to R.E.A.C.H. before you preach.

DEACON TIM HEALY is a deacon for the Archdiocese of Hartford and conducts retreats on forgiveness. DR. JEFFREY J. FROH is a writer and professor of psychology at Hofstra University.