Words Matter

The precision of words is applicable to the diaconate

Deacon Victor Puscas Comments Off on Words Matter

Like a lot of guys, I played baseball in high school. I was what the local college scouts euphemistically called a “defensive specialist.” That was simply a nice way of saying I couldn’t hit. Not yet ready to give up the “glory days” of high school baseball about which Bruce Springsteen famously crooned, I attended pro baseball umpire school in Florida. (There’s a point to this story, I promise!)

When I was at umpire school, I learned that words matter. If a student said, “Y’er out!” instead of “He’s out!” the student would be downgraded and possibly dismissed if the infraction wasn’t subsequently corrected. And, if a batter made a check-swing on a pitch, and the home plate umpire wished to appeal to the first base umpire, the proper phraseology was “Did he go?”; not, “Did he swing?”

Notwithstanding the fact that my wife thinks these distinctions are dumb, the precision of words has some practical application to the diaconate. Indeed, as humans made in the image and likeness of God, we cannot escape the fact that with the divine gift of language has come a great responsibility: Language should mean what it says and say what it means. Nowhere is this more so than in the liturgy.

Words of Mass

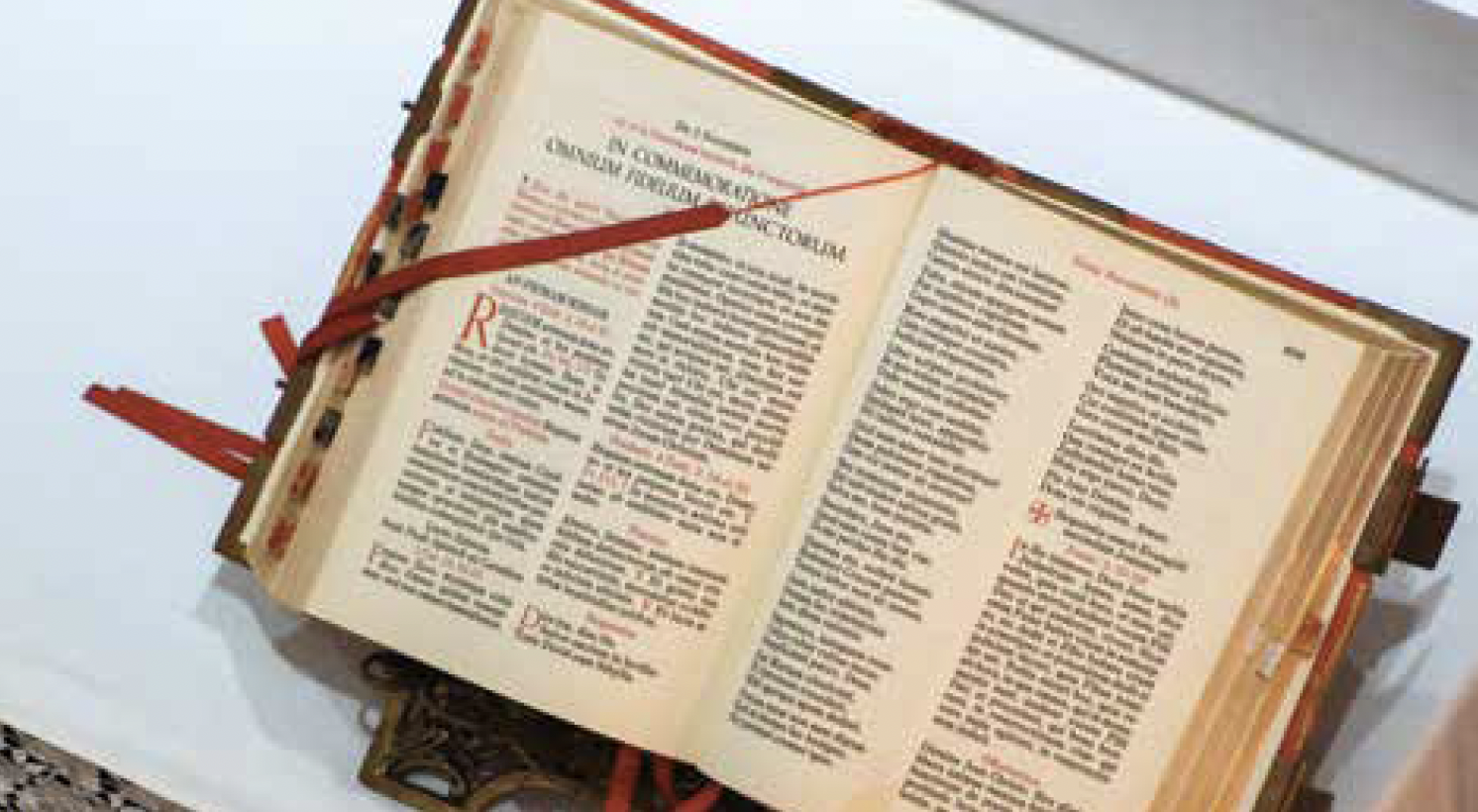

I was recently discussing this with our diocesan archivist who pointed out that we begin Mass “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit,” but we conclude the Mass with “May almighty God bless you, the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit.” Why does the Roman Missal omit “in the name of” at the end of Mass?

Moreover, why do we omit the word “one” at the conclusion of the Collect now? We no longer say, “one God forever and ever”; we say, “God forever and ever.” Yet, at the beginning of the Nicene Creed we say, “I believe in one God.” It seems inconsistent.

Perplexed, I went searching for answers on the web and found an article written by Deacon Tim Kelly in 2015 which says:

“When ordained clergy issues a dismissal-style or solemn blessing, or is requested to give someone a blessing, the clergyman acts to request that God, himself, bless someone. The clergyman does not do the blessing himself. Thus the clergyman issues this blessing on behalf of God by the formula ‘May almighty God bless you, the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit’ while making the Sign of the Cross with his right hand. See, for example, Page 523 of the Roman Missal, ‘The Concluding Rites.’”

This is so because we, as mere mortals, are not doing the actual blessing, per se. We are requesting almighty God to bless them himself; and God does not bless in his own name, he blesses directly — that is, by the infinite, awesome power of the individual and collective authority of the Most Blessed Trinity: the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Note also that the beginning prayer is, “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit” (Roman Missal, Page 365). However, the conclusion, which we as deacons must know for purposes of various prayer sessions, general blessings and especially for concluding Communion services and Liturgy of the Hours, follows the straightforward blessing formula: “May almighty God bless you, the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit.” There is no “in the name of” for this type of blessing. God would never bless “in his own name” … he’s God! He doesn’t invoke his own name, he simply blesses directly from his own authority. He is blessing outright, and thus, when we use or add the “in the name of” in this context, we diminish the power of the blessing to the person receiving it.

The Word ‘Just’

And speaking of diminishing power, as a corollary it is also diminishing and weakening when a deacon prays extemporaneously using the word “just,” as in: “Father, we just ask for your blessing today.” It amounts to a literary crutch that fills the space between thought and spoken word. By eliminating the word just the prayer becomes, “Father, we ask for your blessing today.” It sounds so much stronger. We are his children; he wants us to talk to him and pray unceasingly. Speak up boldly! Be not afraid! His mercy is infinite.

So, whenever possible, leave out just when praying, and remember to utilize the correct formula when issuing a solemn blessing. It will lend much more credibility to our diaconal elocutions. Now, on to the key reason why the Mass was changed on Ash Wednesday 2021.

‘One’ in Prayer

According to the National Catholic Register blog, the reason for the change, put simply, is that the use of the word “one” in the prayer, is not a correct translation from the original Latin text of the Roman Missal. In this light, the congregation’s correction points to an important facet of the liturgy — that how we say our prayers can be as important as what we say in them. With the excision of “one” from the conclusion of the collects, Rome and the English-speaking bishops have addressed not merely a doctrinal issue but a matter of imprecise translation.

This differs from the “one” recited in the Nicene Creed. As Prosper of Aquitane explained in the fifth century, and the current Catechism of the Catholic Church details, “the Church’s faith precedes the faith of the believer who is invited to adhere to it. When the Church celebrates the sacraments, she confesses the faith received from the apostles — whence the ancient saying: lex orandi, lex credendi. … The law of prayer is the law of faith: the Church believes as she prays. Liturgy is a constitutive element of the holy and living Tradition” (No. 1124).

Tradition teaches us, which the Fourth Lateran Council documented, that “we firmly believe and confess without reservation that there is only one true God, eternal, infinite (immensus) and unchangeable, incomprehensible, almighty, and ineffable, the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit; three persons indeed, but one essence, substance or nature entirely simple” (cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, No. 202). Therefore the Creed differs from the Collects. In other words, the faithful could be confused regarding the use of the words “one God” in the Collect as a reference solely to Christ — rather than to his role within the Trinity.

Confused? Well, simply trust that Rome is trying to be as accurate as possible regarding the correct translation from the original Latin text of the Roman Missal, while simultaneously maintaining the Tradition of our doctrines and beliefs.

It’s as simple as the infield fly rule, which is a rule of baseball that treats certain fly balls (other than line drives or bunts) as though caught, before the ball is caught, even if not caught or even if purposely dropped, if there are less than two outs and first and second base occupied or the bases are loaded … phew!

DEACON VICTOR PUSCAS is director of diaconate formation for the Diocese of Joliet, in Illinois. He holds a D.Min. degree from Catholic Theological Union in Chicago.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

ICEL’s Role

The International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL) is a mixed commission of Catholic bishops’ conferences in countries where English is used in the celebration of the liturgy according to the Roman rite. The purpose of the commission is to prepare English translations of each of the Latin liturgical books and any individual liturgical texts in accord with the directives of the Holy See.

Eleven conferences of bishops are currently full members of ICEL, including Australia, Canada, England and Wales, India, Ireland, New Zealand, Pakistan, the Philippines, Scotland, South Africa and the United States of America. — ICEL, icelweb.org/whatis.htm

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..