Dachau and the Diaconate: My Father’s Encounter

How Dachau influenced the restoration of the permanent diaconate

Deacon John Lohrstorfer Jr. Comments Off on Dachau and the Diaconate: My Father’s Encounter

On April 29, 1945, a young 20-year-old, Pfc. John Lohrstorfer, was assigned as an artillery observer for the 232nd Infantry Regiment of the 42nd Infantry Division, nicknamed the “Rainbow Division.” As he was driving his captain near the vicinity of the Dachau concentration camp in Germany, they received a call to report to the camp immediately.

Dachau had been one of the first concentration camps established by the Nazis in 1933 for political prisoners. At one time, it housed over 160,000 prisoners and was later known for medical experimentation. Nothing prepared the young private for the horrors that he witnessed upon entering the camp. Thirty-two thousand surviving prisoners were severely malnourished, starving, diseased and sick. Four thousand bodies were found in a warehouse near a crematorium. They were stacked high like “cords of wood.” Two thousand bodies were found in nearby railroad cars.

Among all these suffering prisoners were hundreds of priests. Priests? Private Lohrstorfer’s first thought was, “What are priests doing in Dachau?” As he found out later, cellblocks 26 and 28 were known as Der Priesterblocks, which housed at one time as many as 2,500 priests, of which 1,000 had already been executed. The Polish chaplain assigned to his American military unit recognized a few names of the priests from his order back home!

These priests were subjected to starvation, hard labor and arbitrary beatings. On one Good Friday, the guards rounded up 60 priests, tied their hands behind their backs and hung them up for several hours. The suffering and pain was great, as many of the priests had their shoulders dislocated after having endured this torture, which was followed by additional beatings.

A Future Restoration?

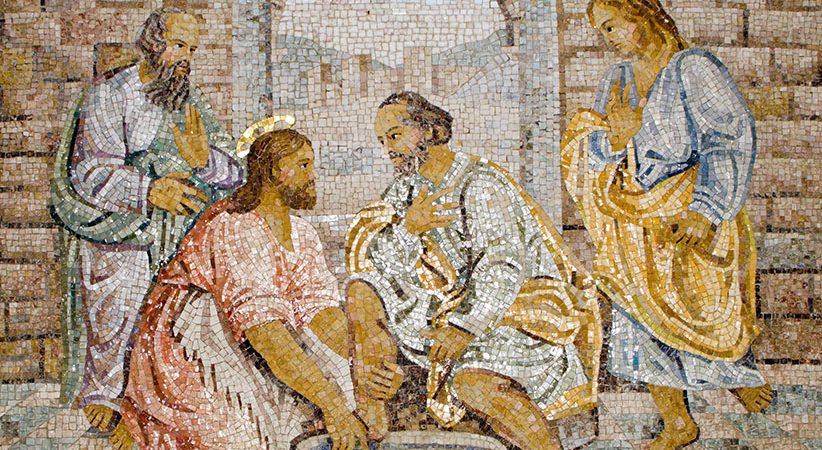

During the years of imprisonment, the priests held clandestine Masses, composed hymns and ministered to one another, as well as to their fellow prisoners. They also reflected on the future of the universal Church and the restoration of a permanent diaconate.

As history tells us, deacons were active through the fourth century, but a decline began in the permanent diaconate at the beginning of the fifth century. By the Middle Ages, the diaconate began to be seen as an intermediate step to the priesthood and no longer an end in itself.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Read More about Dachau in ‘Priestblock 25487’

“Priestblock 25487: A Memoir of Dachau” (Ignatius Press, $15) shares the experience of Father Jean Bernard, who was arrested in May 1941 for denouncing the Nazis and imprisoned in Dachau. The diary, written by Father Bernard and translated into English by Deborah Lucas Schneider, tells the true story of one priest’s survival amid the brutality and torture of a concentration camp. The book was made into a film titled “The Ninth Day” in 2004.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Prisoners Father Wilhelm Schamoni and Father Otto Pies kept notes of their discussions. Father Pies wrote: “We have images of Christ the King and Christ the Priest but maybe what has gone missing is Christ the Servant. For 100 years we have been talking about the possibility of Deacons here in Germany. That is the missing piece and that is how this can come together” (Deacon William Ditewig recounts these events in his book, “The Emerging Diaconate,” Paulist Press, $24.95).

In 1947, Jesuit Theologian Karl Rahner began writing about the possibility of a renewed diaconate. A young German named Hannes Kramer read some of Rahner’s reflections and asked his bishop to ordain him as a deacon. The bishop replied that he couldn’t, but encouraged him to pursue it (cf. U.S. Catholic, “A Call of Their Own: The Role of Deacons in the Church,” June 6, 2014). Kramer formed what was called the “Diaconate Circle” to “study theology and to do service.” These discussions began to spread outside of Germany, resulting in another organization known as The International Diaconate Circle and opened an office in Rome during the Second Vatican Council.

During the 1950s, a Dutch bishop, an archbishop from India and a French priest began a series of talks and presentations on restoring the permanent diaconate and even Pope Pius XII gave an address on Oct. 5, 1957, in which he stated: “We know that there is thought these days to introduce the order of the diaconate. … The idea, at least today, is not yet ripe” (cited in “The Emerging Diaconate”).

Nevertheless, Dachau survivors and original members of the Diaconate Circle wrote a letter to the council fathers in 1962: “Would it not be a living testimony to the Church’s concern for the temporal and supernatural needs of all people to have ordained deacons engage in actual necessities of temporal life to the poor and the suffering, bringing Christ both sacramentally and also in their committed care for the lowly and oppressed in places of neglect and destitution, of hunger and sickness?”

The rest is history as Vatican II made the decision to reestablish the permanent diaconate (cf. Lumen Gentium, No. 29) and those early discussions at Dachau came to fruition.

Spiritual Resistance

The harrowing history of Dachau, melded with the evolution of the diaconate, unveils significant insights and directives for the diaconate’s role in today’s Church. This narrative, marked by the endurance, faith and ministry of priests such as Father Wilhelm Schamoni and Father Otto Pies amid the unimaginable conditions of a Nazi concentration camp, illustrates the remarkable resilience of faith. Their secret celebrations of Mass, the creation of hymns and their pastoral care within the camp were acts of spiritual resistance that not only provided solace to their fellow sufferers but also sowed the seeds for a profound reevaluation of the diaconate’s significance in contemporary Christianity.

Their experiences and subsequent reflections shed light on a pivotal realization for the Church — that is, the pressing need to reclaim and embody the ethos of Christ the Servant. This realization was not born out of abstract theological debate but from the crucible of extreme human suffering and the innate human capacity for hope and renewal. It signaled a shift in understanding the diaconate not just as a liturgical role or a stepping stone to priesthood but as a foundational aspect of the Church’s mission to serve with compassion and humility, mirroring Christ’s own ministry to the least, the lost and the last.

The aftermath of the war and the insights from Dachau catalyzed movements and theological discussions that significantly influenced the Church’s view on the diaconate. Theologians like Karl Rahner and initiatives like Kramer’s Diaconate Circle were instrumental in this shift, advocating for a diaconate that actively engages with the world’s suffering and needs, embodying the Church’s care and service in tangible, impactful ways. This momentum contributed decisively to the discussions at Vatican II, culminating in the restoration of the permanent diaconate, a move that marked a historic recommitment to the Church’s foundational service mission.

In today’s context, the legacy of Dachau and its implications for the diaconate challenge deacons to a deeper understanding and embrace of their identity as servants in the likeness of Christ. It calls them to minister with a heart deeply attuned to the marginalized and vulnerable, driven not by the prospect of ecclesiastical advancement but by the Gospel imperative to serve. Furthermore, it invites deacons to cultivate resilience and find strength in their faith, especially when faced with adversity, drawing from the wellspring of grace that sustained their predecessors in Dachau.

Dynamic Potential

On June 16, 2007, the young soldier who had met and helped so many of the prisoners and priests at Dachau was now 82 years old and present to see his son John Lohrstorfer Jr ordained as a deacon for the Diocese of Kalamazoo, Michigan. What began as a small seed of an idea from a prison cellblock had now reached fruition as his son joined the brotherhood of the diaconate, thanks to the sacrifice of so many priests 62 years earlier.

As the Church moves forward, the evolution of the diaconate from the dark days of Dachau to its revitalization post-Vatican II serves as a powerful reminder of the diaconate’s dynamic potential to address the changing needs of the world while remaining steadfast in the timeless call to service, humility and love.

DEACON JOHN LOHRSTORFER JR. is a permanent deacon for the Diocese of Kalamazoo. He was ordained to the diaconate in 2007.