The Deacon as the Good Samaritan at the End of Life

How accompaniment is essential to integral care of the sick

Deacon Stephen Doran Comments Off on The Deacon as the Good Samaritan at the End of Life

Much has been said about the diaconal call to serve those on the margins in society, bringing Christ to the poor, the prisoners, the homeless, those who struggle with addiction. Yet some of those on the periphery are hiding in plain sight. The sick and especially the dying are often isolated from the Church and the sacraments, not by choice but by circumstance. Isolation breeds loneliness, and loneliness breeds despair. The dying cry out to God. Fellow deacons, listen to this cry.

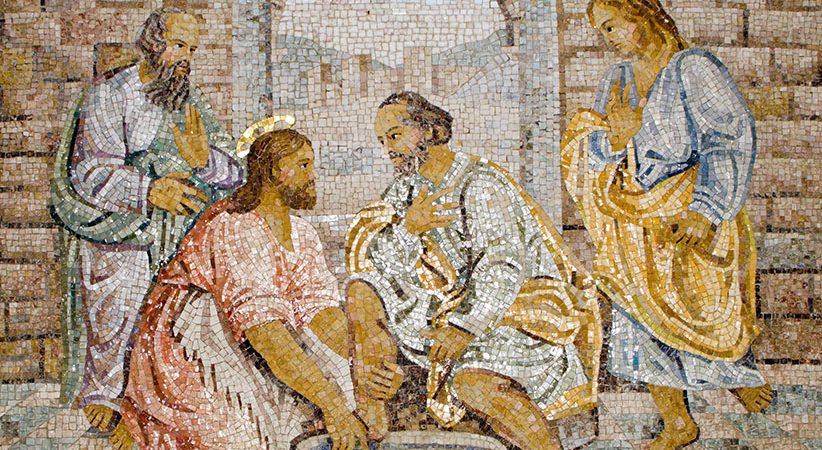

Service to God’s people must be rooted in God’s word, and the parable of the good Samaritan in Luke 10 is a template for accompanying the sick and the dying. For Pope Benedict, the good Samaritan points toward Jesus, the divine physician who “looks into the abyss of human suffering so as to pour out the oil of consolation and the wine of hope” (Feb. 11, 2013).

The good Samaritan is also the icon for the deacon who, as Pope Francis has said, brings “God’s closeness to others without imposing themselves, serving with humility and joy … who gives of himself without seeking the front ranks and has about him the perfume of the Gospel” (June 19, 2021). The deacon, as the good Samaritan incarnate, has a heart that sees: This heart sees where love is needed and acts accordingly.

The Plague of Isolation

During serious illness, patients often feel emotionally and spiritually isolated.

“Death has become medicalized: illness and death are the enemy, and modern technologies are the weapons to defeat them. In the battle against death, the patient is often reduced to an interested bystander whose humanity and personhood are largely ignored. When a person is in the hospital, he is a medical problem to be solved,” I explained in my book “To Die Well: A Catholic Neurosurgeon’s Guide to the End of Life” (Ignatius Press, $17.95).

This medicalization of illness and death is an assault on the patient’s dignity and exacerbates the isolation often experienced during serious illness, especially as death approaches. The soul that is isolated is prey for the evil one, who lurks at the holiest moments in our lives. To accompany someone during this time is a place of privilege for the deacon.

Isolation is a scourge of the modern world. Despite an abundance of devices that virtually connect us, never before have people felt so alone. In 2023, the surgeon general issued a report on the epidemic of loneliness and isolation. Approximately half of U.S. adults report experiencing loneliness. Social isolation is associated with a significantly increased risk for early death from all causes. Lacking social connection can increase the risk for a premature death as much as smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day. Chronic loneliness and social isolation can increase the risk of developing dementia by 50% in older adults. Loneliness and low social support are also associated with increased risk of self-harm, and in older adults an increase in loneliness was reported to be among the primary motivations for self-harm.

The most disastrous expression of self-harm is suicide, which as the Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches is an affront to the dignity afforded to all human life and is contrary to the love of God. However, the Catechism acknowledges that moral responsibility may be reduced under certain circumstances and cautions against despair for the salvation of the deceased; God’s ways are not our ways, and he alone is the judge (cf. Nos. 2280-83).

Assisted Suicide/Euthanasia

It is safe to say that suicide is seen by most people as a tragedy, yet when presented as “assisted suicide” the word somehow takes on a new meaning, implying compassion and mercy. Assisted suicide and euthanasia technically differ but are morally equivalent. Assisted suicide occurs when one person helps another person commit suicide but does not perform the action that leads to the other’s death. Typically, a physician prescribes medications to the person wishing to die but does not administer those medications. Euthanasia is performed when someone actively participates in the death of the other: a physician or nurse infuses lethal medications in the veins of the person wishing to die. The intention of the parties involved is at the heart of the matter.

There really is no ethical distinction between assisted suicide and euthanasia because both intend the death of someone, so for practical purposes, the terms are interchangeable. Ironically, euthanasia is literally translated from the Greek as “good death.”

In the United States, assisted suicide is legal in 10 states and Washington, D.C. In 1994, Oregon became the first state to allow patients to kill themselves with the aid of medical professionals, and its laws have served as a template for other states that followed.

In Canada, direct killing of patients by euthanasia was legalized in 2016 and goes by the euphemism Medical Aid in Dying (MAID). In both the United States and Canada, the number of individuals seeking assisted suicide or euthanasia has grown significantly in recent years. According to the most recent statistics from the Canadian government, 13,241 people were euthanized in 2022 alone and MAID now accounts for over 4% of total deaths. Since MAID was legalized in 2016, 44,958 people have been killed. The most recent annual report from the state of Oregon shows that the number of patients dying at the hands of medical professionals has increased by 500% in the past 10 years.

One common misconception is that people seeking euthanasia do so primarily because of intractable pain. While this can be the motivating factor for some people, it is not the most common reason. Although loss of autonomy or the ability to engage in meaningful activities are the most common concerns, nearly 1 in 5 people report loneliness as the nature of suffering of those who received MAID in 2022. As queried in a 2022 editorial in the British Medical Journal, “Will euthanasia and assisted suicide be offered as the societal response to devaluation, emotional seclusion, and loss of social significance experienced by our fellow human beings who experience loneliness? Will help and human affection be replaced by the offer of planned death? Is this a civilized response?”

Deacon as Good Samaritan

If loneliness is the plague of modern culture and a driving force behind euthanasia, what then is the antidote? According to the surgeon general’s report, isolation and loneliness have a comparable, if not greater, impact on survival than risk factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, hypertension and obesity. Meanwhile, social connection increases survival rates by 50%. In other words, those with meaningful relationships live substantially longer than those who are isolated and lonely. The surgeon general’s first pillar to improve social connection is to strengthen the social infrastructure in local communities and invest in local institutions that bring people together.

Local communities that bring people together? Sounds a bit like the Church. But, of course, the Church is more than that. It is the bride of Christ that pours out the salvific love of the Trinity. That love is made manifest not only through the Mass and the sacraments, but also through the members of the Church, the mystical body of Christ. In his capacity as the Church’s envoy, the deacon has a particularly powerful role in combating the cancer of isolation and its most deadly consequences. Propelled by service at the altar, he must listen to and respond to the cry of the sick and dying.

The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, in a letter focusing on the care of the dying: “The parable of the Good Samaritan shows what the relationship with the suffering neighbor should be, what qualities should be avoided — indifference, apathy, bias, fear of soiling one’s hands, totally occupied with one’s own affairs — and what qualities should be embraced — attention, listening, understanding, compassion and discretion.

“The invitation to imitate the Samaritan’s example — ‘Go and do likewise’ (Lk 10:37) — is an admonition not to underestimate the full human potential of presence, of availability, of welcoming, of discernment and of involvement, which nearness to one in need demands and which is essential to the integral care of the sick.

“The quality of love and care for persons in critical and terminal stages of life contributes to assuaging the terrible, desperate desire to end one’s life. Only human warmth and evangelical fraternity can reveal a positive horizon of support to the sick person in hope and confident trust” (Samaritanus Bonus, No. 10).

The deacon is the good Samaritan for our times, bringing God’s closeness to others at the time of greatest need, pushing away isolation and loneliness, pouring out the oil of consolation and the wine of hope.

DEACON STEPHEN DORAN, M.D. is a neurosurgeon with over twenty-five years of experience and serves as the bioethicist for the Archdiocese of Omaha. His latest book is “To Die Well: A Catholic Neurosurgeons Guide to the End of Life” from Ignatius Press.