Inner Healing

To be free of our wounds, we must first acknowledge them

Deacon Robert T. Yerhot Comments Off on Inner Healing

Who are you, and what are you to do? These are questions of identity and mission. We all can and must ask these questions. We pondered them at length during our diaconate formation. How well did we answer then? How well do we answer now?

I believe it is only in freedom that we can honestly answer these questions — only if we are free from our wounds.

Nowadays, so many clergy and men in formation live in great confusion as to who they are and how they are to live. This confusion is creating so much division in our world, so much division in our culture, and so much division in our personal lives. We can even see it in the Church.

Said in a different way, I think our world is deeply wounded, and so are we. We all need healing, and we all must acknowledge this.

Who are we, and what are we to do? Do you recall how Pope Francis answered a similar question put to him shortly after his election as pope? A journalist wanted to get to know the new pope, so he asked, “Who is Jorge Mario Bergoglio?” How did Pope Francis respond? He said, “I am a sinner” (and I paraphrase now) in need of God’s healing mercy. The pope would go on a few years later to give us a Year of Mercy, focusing on mercy and forgiveness, a whole year during which we were asked to reflect upon our wounded identities and seek inner healing so as to be better prepared to go on mission.

We deacons can assist those desiring to be free from shame, wounds and sin only if we first receive healing. We can assist others to resist the lie that God will love them only if they are “fixed” of their past sins and wounds. We can assist others to embrace the truth that God loves them and redeems those sins and wounds. We can do this only if we, too, embrace this truth about ourselves. God loves us in our wounds, and, with the assistance of the human interventions so often needed, his grace can heal us and make us whole.

The Challenge

As I explained in my column in the March/April issue of this magazine (“Walking Wounded”), one question comes up again and again in my work as a spiritual director for clergy and men in formation: “What is impeding my progress, Deacon?” While part of the answer to that question is particular to each individual, I have found that just about every impediment is rooted in common ground. I have come to understand that ground as unacknowledged, unhealed wounds.

With rare exception, men who are entering our formation programs, and clergy already in ministry, are impeded by spiritual, relational and emotional wounds, which are expressed in virtue struggles, patterns of sin, distracted disintegrated interior lives, and inhibited intimacy with God and others. Unhealed, these wounds will continue to impede depth in the interior life and fruitfulness in active ministry.

One difficulty I find in communicating this is the persistent denial of the nature and deleterious effects of contemporary American culture on men. Simply put, our culture is toxic to spiritual depth and affective maturity. Yet clergy and men in formation often struggle to acknowledge their wounds, either denying them outright (“I am not affected by cultural sin.”) or minimizing them (“My wounds are not that bad.”). Denial and minimization are barriers to the deep healing that is needed for fruitful ministry. They are open doors through which Satan enters men’s lives. We wonder why good men do bad things — is it partially due to our explicit or implicit denial of the significance of our wounds?

Psychology and Theology

Many spiritual directors are hesitant to explore this area with men because it requires a competency and familiarity with the behavioral sciences. Men steeped in theology and spirituality often view the language and concepts of psychology, clinical social work and therapy with suspicion.

Some formators will explicitly say, and others will imply, that psychology is fine and good, but spiritual and moral theology are more important. I think this indicates a defective understanding of the human person within the context of Christian anthropology. A sound theological understanding of the human person can better inform the behavioral sciences, which in turn can better inform the theology. A more robust and comprehensive exchange between the two is needed.

Having said that, I gratefully acknowledge that the mutual suspicion between psychology and theology is diminishing in more and more houses of formation. Fully credentialed psychologists and others are increasingly present and associated with diaconate formation programs, college- level seminaries and schools of theology, and no longer seen as exceptional consultors. In these programs I would include the diaconate program of the Diocese of Winona-Rochester, the Immaculate Heart of Mary Seminary in Winona and the St. Paul Seminary in St. Paul, all in Minnesota. Men well-versed and credentialed in both psychology and theology are key in articulating a common coherent language in both fields.

Path to Healing

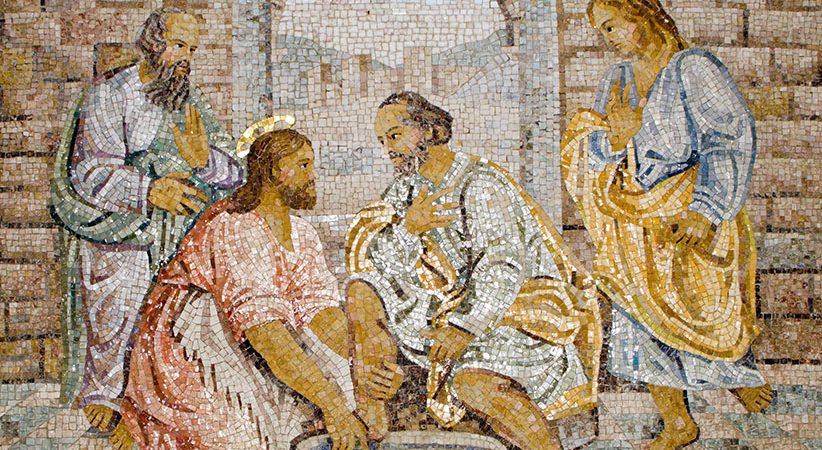

What is the path to healing? To answer that question, one needs to define healing. The Scriptures suggest an answer in St. Mary Magdalene. It was only after a radical encounter with the incarnate God, Jesus Christ, that Mary found freedom from the many wounds of her life. So, on a foundational and spiritual level, healing entails accepting undeserved grace found in an encounter with Jesus Christ.

Most healing that we experience with such an encounter is not the removal of the wound and its effects, but a redemptive healing, in which God takes our wounds and redeems them — buys them back if you will — and places them at the service of his salvific plan for the entire world.

In redemptive healing, we continue to carry the scars of our wounds, but we have been freed to go and place them at the service of others. One great example of this are men who have gone through the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous and now serve as sponsors for others. These are wounded men, no doubt, but always at the service of another, seeking freedom from alcoholism.

Redemptive healing also brings a previously unknown clarity and awareness of how our wounds are a part of salvation history, our own and the world’s.

There is great freedom in such awareness. Our Blessed Mother knew this freedom as she stood beneath the cross: She knew that the cross was part of salvation history, and thus she could stand there in witness to all her son was accomplishing for the world.

When we experience redemptive healing, we discover a renewed freedom to love as God loves and to remain in communion with others in their suffering. Psychologically, we may experience freedom from anxiety and doubt, freedom from impulsive or compulsive behaviors, freedom from addictions and clarity of thought. Relationship stability and a sense of security increase.

Practical Steps

I would offer the following practical steps to move toward healing. These must not be done in isolation, but always with the accompaniment of a spiritually wise and psychologically competent guide.

Step one: Be humble and beg for the grace to accept that you are wounded. As simple as this may sound, it is often a huge barrier for men. We carry a cultural expectation of invulnerability to the effects of others’ sins. We identify too closely with our wounds, and we protect ourselves from the shame attached to them. This leads us to deny who we are — that is, wounded but beloved sinners in need of God’s merciful healing. Step one is always humility before God and others.

Step two: Your wounds do not define you. God does. Ask yourself, “To what image of God am I attached?” Don’t give a theological response, but one that arises from your personal relationship with God. How have you experienced him? How does the image you carry within you of your earthly father — with whom we identify, for good or ill — affect your image of your eternal Father? Reflect, pray and journal your conclusions.

Step three: Beg for the grace to know the roots of your suffering, the origins and patterns of sin in your life, your fears in regard to them, the secrets you have kept because of them, and the lies you have accepted from our culture and the individuals who have sinned against you. Do a personal inventory of these wounds. Take time to look within yourself. When have you felt overwhelmed or neglected?

When have you experienced pain? Have you been exposed to violence in your family, your community or online? How many surgeries have you had, how many chronic illnesses have you suffered, how many physical insults have you sustained? How were you disciplined as a child? Are you a veteran with combat exposure? Have you experienced periods of moral scrupulosity, shame or lax conscience? What have been sources of doubt in your life? Did these doubts arise from credible sources or from the deception of others? Note all these in your inventory.

Step four: Share your wound inventory first with God and then with your spiritual director. Trust them both. This is where competent spiritual direction is so important.

Step five: Beg for the grace of healing and the courage to live in freedom. Again, as simple as this may sound, it can be a difficult step for many men. We tend to recoil from “begging.” It implies dependency. But it is through such a dependency on grace and the gift of courage that healing can begin.

Step six: Resolve each day to live a life of freedom in the Lord, and to remain in spiritual direction as you more fully enter into a deep relationship with God. Seek out psychological assistance when needed. Remain faithful to the guidance of those God has placed in your life.

So, we end where we began. Who are we and what are we to do? These fundamental questions about identity and mission are answered only in the context of our relationships with God and others. If our ability to maintain communion with God and others is sufficiently impeded by unhealed wounds, we will not be able to give good answers to those questions; we will be uncertain about our identities and our mission in life. Freedom and clarity in our responses are found in Jesus Christ and those skilled men and women he places in our lives.

God bless and keep each of you!

DEACON ROBERT T. YERHOT, MSW, is the Director of the Diaconate for the Diocese of Winona-Rochester. He is a core-group member of the Institute for Diaconal Renewal in Steubenville, Ohio. A spiritual director for clergy, he has published articles on diaconal spirituality.